It’s a reality that male writers are taken more seriously than women writers. All anyone needs to do to become disheartened is read the Vida numbers. Trust me, I wish I could laugh when The Washington Post’s Ron Charles talked about “women gossiping about how their little books are treated by media,” except that too much of his totally hip book review was spot on. Still I’m comforted to know that attitudes about equality among men and women do change–and have–through respectful discourse. To that end, I do my part to make a difference, working to empower our girls to use their voices and, like many educators, I use new research to focus my attention on how we socialize our boys. As a novelist, I’ve parlayed my experience as a family therapist into writing about the emotional and sometimes dark side of relationships in an effort to connect men and women any way I can. Recent studies confirm what every novelist knows: “The novel is an unequaled medium for the exploration of human social and emotional life.”

It’s a reality that male writers are taken more seriously than women writers. All anyone needs to do to become disheartened is read the Vida numbers. Trust me, I wish I could laugh when The Washington Post’s Ron Charles talked about “women gossiping about how their little books are treated by media,” except that too much of his totally hip book review was spot on. Still I’m comforted to know that attitudes about equality among men and women do change–and have–through respectful discourse. To that end, I do my part to make a difference, working to empower our girls to use their voices and, like many educators, I use new research to focus my attention on how we socialize our boys. As a novelist, I’ve parlayed my experience as a family therapist into writing about the emotional and sometimes dark side of relationships in an effort to connect men and women any way I can. Recent studies confirm what every novelist knows: “The novel is an unequaled medium for the exploration of human social and emotional life.”

Though I don’t bristle at the term “women’s fiction” I do see it as narrow and exclusive. In a culture where we’re forever dishing about wanting a sensitive partner, do we really want men to think (or anyone to reinforce) that what women read is for their eyes only?

In an op ed reflecting on the fifty years since Betty Friedan’s seminal work on feminism, Stephanie Coontz, a noted historian and teacher of family studies, claims that the progress toward gender equity no longer lies in changing personal attitudes. Tell that to David Gilmour, who recently set social media on fire with his statements about why he doesn’t teach fiction written by women. No doubt we will always need to force attitudinal change with loud and clear voices, yet we must break down structural barriers to equity too. Readers and writers can play a role by merely turning the label women’s fiction on its head.

Nearly a year ago, Meg Wolitzer wrote an essay that got me thinking about how the term excludes. Nine times out of ten, the first question a reader asks when he or she learns I’m a novelist is, “What’s the book about?” Never once since I began writing fiction have I been asked about genre by anyone outside of publishing. If you’re aligned with Wolitzer’s thinking, that the women’s fiction label can relegate novels to second class status, why not consider a genre makeover?

I propose that like science fiction (fiction about science) and mystery fiction (fiction about a mystery) that we use the term fiction about family. #FamFic if you’re into hashtags. Take a look at the copyright page of any of your favorite family dramas and you’ll find the Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data already does this. The first category listed in Justin Torres’s We The Animals is family. For Wally Lamb’sThe Hour I First Believed, Pam Houston’s Contents May Have Shifted, and Steve Yarborough’s The End of California you’ll see family fiction’s synonym, domestic fiction. And if you’re one to frequent Amazon, you’ll find family life fiction is a prominent label categorizing novels online.

So for readers who’ve got to have their labels–who are opposed to fiction just being fiction– fiction about family ticks all the boxes. Without playing the sexism card, it gives women the heads up a book is for them. And it tells men, this one’s for you too. Research shows that when anyone reads fiction, neurologically speaking, our emotional state is positively impacted. Reading trains our brains to work more efficiently. And better brains, lead to stronger hearts, and thus more compassionate action.

Women shouldn’t be the only ones reading about families. Without a doubt there are lots of good reasons for men to read fiction. In the thirty years I’ve counseled families, I’ve seen firsthand how family life education of any kind leads to positive attitudes toward motherhood and fatherhood, changing the way we think about children.

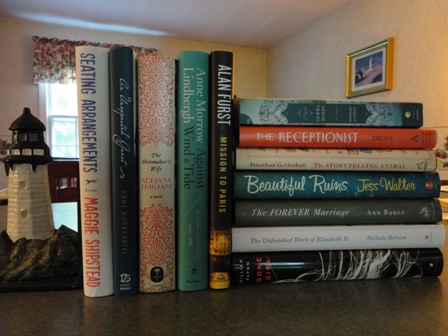

We all want to help women and men become better women and men. If we were to embrace a gender-neutral genre called fiction about family, then writers included in this category would be Meg Wolitzer and Jonathan Franzen, Chris Bojahlian and Jody Picoult, Joshua Henkin and Elizabeth Strout. Wally Lamb, Lionel Shriver, and the list goes on and on.

If you believe like I do that words matter and that novels have the power to influence attitudes about everything from the politics of childcare to understanding addiction, then join me at LitChat.com for conversations about good books. Let’s use our voices to change the way we think about men and women and fiction about family. (#FamFic if you’re into hashtags)